All right. Let’s get a look at you. Gotta figure out what the cringe-to-awesome ratio is.

I didn’t actually watch the Nintendo Direct broadcast when it first came out, ‘cause it was, like, the middle of the night in New Zealand and I’d been squinting at passages from Herodotus for two hours, so my immediate reaction was “I’m gettin’ too old for this $#!t.” So now you get to experience my first impressions of the broadcast as I watch it.

Brace yourselves.

Oh hi there, Satoru Iwata. Sure, I’ll listen to your… whatever. Knock yourself out.

Yay for nostalgia time. You know, I’ve always had mixed feelings about the whole two-versions thing, but he’s right, it does promote trading, and thereby interaction between players, and helps keep Pokémon from being a solitary pursuit… just as long as the damn link cable keeps working.

You have all the cool stuff from Gold and Silver to choose from, and you pick “shiny Pokémon” as the thing that defines that generation for you? Ah, whatever floats your boat, I guess.

Yes, double battles were cool, and it was neat that Ruby and Sapphire were released overseas so much more promptly than their predecessors. The wireless adapter that came with Fire Red and Leaf Green was great too, because it actually worked. You’re right, Iwata, that was a big step. Um… you don’t have any thoughts on the decision to remake Red and Blue? No? Okay, that’s cool.

And you’re rushing through the rest of the games. Yeah, I guess you’re tired of the retrospective stuff. Fair enough, I guess. Time to talk about the new 3DS games.

Hey, Pikachu; how’re you doing? Yeah, yeah, I know you’re excited, Iwata just told us OH MY GOD DID YOU JUST ELECTRIFY THE EIFFEL TOWER?

Right, trailer starts in earnest. We have mirrors, that’s pretty. And a full-sized player character image instead of a dinky little sprite, that’s a first. And… wow, okay. Yeah, I don’t know if “breathtaking” is totally fair but that is pretty. And… it looks like we actually are in France, because that doesn’t look exactly like the Eiffel Tower, but it’s close, and Pikachu was definitely in France. New region is based on Europe, I guess, the way Unova was based on New York? That’s kinda cool; I like Europe. (Please let there be a town based on Athens, please let there be a town based on Athens) Also our running shoes have been replaced with roller skates. That’s… actually kinda awesome.

AND STARTERS, with their foreign language names already set, no less. The Grass-type… Chespin, who is… I guess like a chipmunk with a chestnut helmet? And- oh, wow is that the battle interface? *ahem* Sorry. The Fire-type… Fennekin, who is… a fire-fox, which… well, yeah, y’know, that was kinda Vulpix’s thing, guys, and… yeah, okay, it sort of looks like you’ve given it psychic powers as well, which… was also Vulpix’s thing to an extent, and also Zorua’s as well, sort of, but I guess foxes are kind of important in Japanese culture and mythology so I’ll reserve judgement on that one. And, the Water-type… Froakie, who is… a frog. Well. All right. I’m guessing they never read my entry on Seismitoad but it’s not like I was expecting them to. Maybe they’ll do something else with Froakie besides give him sonic powers.

I see… lots of cool forest, a wild Pikachu, some other ‘traditional’ Pokémon… they seem to be making a point of that. I suppose that means they’re not going to do a Unova again and bar old Pokémon from their new region; hallelujah. WHOA raging columns of fire; please don’t tell me that’s a Gym; I don’t want to be bacon. And… okay, these are the new legendary Pokémon, I imagine. Giant… evil… Y-shaped bird… getting kind of a vulture vibe from this thing? I kinda think that designing a Pokémon specifically so it looks like the letter Y when seen from below is sort of a stupid design choice but it doesn’t impact too much on vulture-mon’s appearance from other angles, so I’ll let them have that one. And his counterpart… the blue crystal rainbow stag thing. Okay. Sure. Why not? I’m not really sure what they’re trying to go for with this one, because the choice of a stag and the forest setting seem to imply they’re aiming for the old ‘nature guardian’ archetype but the whole rainbow crystal aesthetic doesn’t seem to mesh with that. Hmm. I wonder what they have in mind there?

Pokémon X and Pokémon Y? Okay, so I guess you’ve finally run out of colours. After Black and White I suppose anything else would have started sounding forced. Speaking of which, there must be something significant in those names, since they wouldn’t abandon the traditional naming scheme without good reason, particularly after Black and White had such significant titles (the central theme of those games being duality, and the reconciliation of dualities). Only… what the hell do X and Y signify? Only thing that comes to mind for me is the two axes of a Cartesian plane, which… hmm. Well, they are making rather a lot of the 3D-ness of it all, as they usually do. Given that, I suppose it would make sense to have three games, X, Y, and Z to represent the three spatial axes of a three dimensional world. It doesn’t exactly have the same delightful symbolic resonance as Black and White, but I suppose I should wait for the games to come out so I can experience the plot before I give a final word on that. Based on the flaring of the letters in the logo, it looks like stag-dude’s antlers are supposed to recall the shape of an X the way birdie’s wings form a Y-shape, so… I guess they could be going for a land-and-sky thing based on X as the horizontal and Y as the vertical. Kinda paints them into a corner with Z, though, since Z is just… y’know… the other horizontal direction.

And you’re giving it a single release date for Japan and overseas! Wow, you’re really committed to this, aren’t you, Nintendo? Er… wait. Japan, the Americas, Europe and Australia. Um. Hello? New Zealand here? Um… are we Australia now? Guys?

Oh, whatever. Yes, thank you very much too, Iwata, that was… interesting.

Hmm.

This is either going to be amazing and wonderful, or a catastrophic waste of time and resources.

Possibly both.

I have to review the new Pokémon, don’t I? All of them? It’s, like, my schtick, isn’t it? And I have to do the whole “I hereby affirm/deny this Pokémon’s right to exist” thing again?

…great. Well, that’s my project for all of 2014.

I’m not totally sure what to make of this. I am made slightly uneasy by the emphasis the trailer puts on the visual aspects of the games, and the amount of work that’s going into a complete redesign of the graphics. I mean, I’m sure the games will be visually stunning, and that’s nice, don’t get me wrong, but I don’t really care all that much; I was totally happy with the old Ruby/Sapphire graphics engine. Still, that doesn’t mean they won’t be paying attention to the other aspects of the games. The graphics of Black and White were hyped too, and that didn’t stop them from having the best story the series has yet produced (continuing to reserve judgement on Black and White 2, since I still haven’t finished playing).

So I suppose my final word on this is that I don’t really do optimism, as a rule, but Pokémon X and Y haven’t made me want to beat my head against the wall. Yet.

Although I hadn’t quite had it in mind originally, these entries on the Pokémon Power Bracket eventually evolved into something akin to a discussion of what I think legendary Pokémon should and should not be. Given the direction this project ended up taking, I suppose that I now ought to talk about these questions in more general terms and lay out, once and for all, what opinions I hold on these mysterious creatures and why.

Although I hadn’t quite had it in mind originally, these entries on the Pokémon Power Bracket eventually evolved into something akin to a discussion of what I think legendary Pokémon should and should not be. Given the direction this project ended up taking, I suppose that I now ought to talk about these questions in more general terms and lay out, once and for all, what opinions I hold on these mysterious creatures and why. Legendary Pokémon are significantly tougher and have more powerful attacks than the vast majority of ordinary Pokémon (Dragonite, Tyranitar, Salamence, Metagross, Garchomp and Hydreigon have stat totals that match or exceed those of some legendary Pokémon, and are often called ‘Pseudo-Legendary’ for this reason). Big numbers don’t make the Pokémon, of course: consider Articuno, whose type combination carries a number of crippling weaknesses and whose movepool is small and inflexible. Most members of the lowest ‘tier’ of legendary Pokémon are like this: theoretically powerful, but limited (there are also a couple, like Entei and Regigigas, who are just plain bad, but that’s really a topic for another day). That’s all well and good. It’s the really powerful ones that concern me: Mewtwo and Ho-oh and the like; Kyogre and Arceus most of all. These Pokémon clearly aren’t meant to be ‘balanced’ in any meaningful sense – possibly not even against each other. They don’t merely have a slight edge over mortal Pokémon; they can steamroll entire teams if played competently. Now, I’ve always contended that game balance has never really been a ‘thing’ in Pokémon anyway; I simply don’t believe it was ever part of the designers’ aims. However, it doesn’t take a genius to see that this legendary élite will quickly take over any context to which they are introduced; Nintendo themselves recognise this and ban most of them from official tournaments and in-game battle facilities. Outside of official contexts, however, any ban-list must be self-policing, which is a recipe for chaos – particularly since Nintendo’s ban-list, while a reasonable starting point, is riddled with flaws (they regularly ban Phione, for goodness’ sake). Some fan communities produce and regularly update tier lists to define which Pokémon should and should not be allowed, but one need only consider the vitriol directed against Smogon University for banning Blaziken to see that this is hardly a perfect solution. Some would consider it the height of lunacy to ban Celebi while allowing Excadrill (as Nintendo does); others would think it perfectly rational. As a result of all this, I cannot help but regard legendary Pokémon as a negative influence on the games’ ability to function as intended.

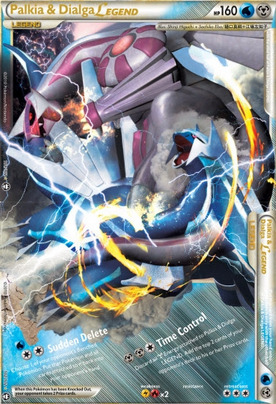

Legendary Pokémon are significantly tougher and have more powerful attacks than the vast majority of ordinary Pokémon (Dragonite, Tyranitar, Salamence, Metagross, Garchomp and Hydreigon have stat totals that match or exceed those of some legendary Pokémon, and are often called ‘Pseudo-Legendary’ for this reason). Big numbers don’t make the Pokémon, of course: consider Articuno, whose type combination carries a number of crippling weaknesses and whose movepool is small and inflexible. Most members of the lowest ‘tier’ of legendary Pokémon are like this: theoretically powerful, but limited (there are also a couple, like Entei and Regigigas, who are just plain bad, but that’s really a topic for another day). That’s all well and good. It’s the really powerful ones that concern me: Mewtwo and Ho-oh and the like; Kyogre and Arceus most of all. These Pokémon clearly aren’t meant to be ‘balanced’ in any meaningful sense – possibly not even against each other. They don’t merely have a slight edge over mortal Pokémon; they can steamroll entire teams if played competently. Now, I’ve always contended that game balance has never really been a ‘thing’ in Pokémon anyway; I simply don’t believe it was ever part of the designers’ aims. However, it doesn’t take a genius to see that this legendary élite will quickly take over any context to which they are introduced; Nintendo themselves recognise this and ban most of them from official tournaments and in-game battle facilities. Outside of official contexts, however, any ban-list must be self-policing, which is a recipe for chaos – particularly since Nintendo’s ban-list, while a reasonable starting point, is riddled with flaws (they regularly ban Phione, for goodness’ sake). Some fan communities produce and regularly update tier lists to define which Pokémon should and should not be allowed, but one need only consider the vitriol directed against Smogon University for banning Blaziken to see that this is hardly a perfect solution. Some would consider it the height of lunacy to ban Celebi while allowing Excadrill (as Nintendo does); others would think it perfectly rational. As a result of all this, I cannot help but regard legendary Pokémon as a negative influence on the games’ ability to function as intended. It is partly for this reason that I expect rather a lot of them elsewhere. Legendary Pokémon are, well, legendary; that is, they are the subject of legends, myths, traditions and tales. As a result they are a fundamental part of the culture, history and philosophy of the Pokémon world and serve to expand our understanding of that world. Provided they do a good job of it, tell a good story, I am generally willing to give them some latitude to act as game-breakers when they take the field; they’ve ‘earned it,’ in a sense (especially ones that aren’t actually game-breaking, like Zapdos and Suicune). This is not always an easy thing to judge. I maintain that it was the second generation that got it right, with the story of Entei, Suicune and Raikou, who were killed in the fire that destroyed the Brass Tower and drove Lugia away from Ekruteak City, and then resurrected by Ho-oh with incredible new powers. These Pokémon all have a history that ties them in with the past of their home region and its visible remnants, while hinting at fantastic powers beyond what ordinary Pokémon can harness. Articuno, Zapdos and Moltres contribute to the general feel of the games with their aura of mystery, but don’t do so with the same eloquence or sophistication as their successors, while many later legendary Pokémon simply go too far. Ever since Ruby and Sapphire, Game Freak seem to have gotten it into their precious little heads that a good plot must be ‘epic’ and that one of the requirements of ‘epic’ is an impending apocalypse (neither of which is actually true), so naturally they’ve been designing legendary Pokémon to match – Kyogre and Groudon, Dialga and Palkia, Arceus, Reshiram and Zekrom – as though their games won’t be complete without Pokémon capable of destroying the nation, the world, or even the universe. This isn’t even a flawed concept, in principle. The flaw is in the way it interacts with the games’ premise and central tenet: “gotta catch ‘em all.” If these Pokémon truly were as remote and aloof as they are often portrayed, present in the game as forces to be deflected or mitigated, I would not have any major objections to them; many of them have interesting stories, and they could definitely add something to the setting’s cosmology. The problem is that once something exists in Pokémon, you have to be able to catch it; otherwise the whole mess falls apart.

It is partly for this reason that I expect rather a lot of them elsewhere. Legendary Pokémon are, well, legendary; that is, they are the subject of legends, myths, traditions and tales. As a result they are a fundamental part of the culture, history and philosophy of the Pokémon world and serve to expand our understanding of that world. Provided they do a good job of it, tell a good story, I am generally willing to give them some latitude to act as game-breakers when they take the field; they’ve ‘earned it,’ in a sense (especially ones that aren’t actually game-breaking, like Zapdos and Suicune). This is not always an easy thing to judge. I maintain that it was the second generation that got it right, with the story of Entei, Suicune and Raikou, who were killed in the fire that destroyed the Brass Tower and drove Lugia away from Ekruteak City, and then resurrected by Ho-oh with incredible new powers. These Pokémon all have a history that ties them in with the past of their home region and its visible remnants, while hinting at fantastic powers beyond what ordinary Pokémon can harness. Articuno, Zapdos and Moltres contribute to the general feel of the games with their aura of mystery, but don’t do so with the same eloquence or sophistication as their successors, while many later legendary Pokémon simply go too far. Ever since Ruby and Sapphire, Game Freak seem to have gotten it into their precious little heads that a good plot must be ‘epic’ and that one of the requirements of ‘epic’ is an impending apocalypse (neither of which is actually true), so naturally they’ve been designing legendary Pokémon to match – Kyogre and Groudon, Dialga and Palkia, Arceus, Reshiram and Zekrom – as though their games won’t be complete without Pokémon capable of destroying the nation, the world, or even the universe. This isn’t even a flawed concept, in principle. The flaw is in the way it interacts with the games’ premise and central tenet: “gotta catch ‘em all.” If these Pokémon truly were as remote and aloof as they are often portrayed, present in the game as forces to be deflected or mitigated, I would not have any major objections to them; many of them have interesting stories, and they could definitely add something to the setting’s cosmology. The problem is that once something exists in Pokémon, you have to be able to catch it; otherwise the whole mess falls apart.

Which legendary Pokémon are effective additions to the world, in my view (aside from the second-generation ones I’ve mentioned)? Mewtwo is one; though the extent of his powers is difficult to gauge, his backstory was clearly written with ideas of morality and identity in mind, and he also allows us to ask interesting questions about the relationship between humans and Pokémon. This, I think, is the sort of thing that Pokémon is actually rather good at, simply because the basic premises of the franchise are so interesting from an ethical standpoint. Regirock, Regice and Registeel, though I’ve always felt they are distressingly emotionless, making them difficult to relate to, have a fascinating backstory that gives us a new perspective on the way people related to Pokémon in the past, and what that might mean for the future (arguably, the very thing that bugs me about them actually makes them more effective, their alien countenance emphasising how far they stand apart from humanity). They recognise, as well, that the power to shape worlds is not actually a requisite for winning the fear or adoration of an ancient civilisation. Tornadus, Thundurus and Landorus, too, have destructive and protective powers that function on a local rather than a regional or global scale; they are deities of folktale, not epic, a smaller scale of things to which Pokémon, by its very nature, is eminently better-suited.

Which legendary Pokémon are effective additions to the world, in my view (aside from the second-generation ones I’ve mentioned)? Mewtwo is one; though the extent of his powers is difficult to gauge, his backstory was clearly written with ideas of morality and identity in mind, and he also allows us to ask interesting questions about the relationship between humans and Pokémon. This, I think, is the sort of thing that Pokémon is actually rather good at, simply because the basic premises of the franchise are so interesting from an ethical standpoint. Regirock, Regice and Registeel, though I’ve always felt they are distressingly emotionless, making them difficult to relate to, have a fascinating backstory that gives us a new perspective on the way people related to Pokémon in the past, and what that might mean for the future (arguably, the very thing that bugs me about them actually makes them more effective, their alien countenance emphasising how far they stand apart from humanity). They recognise, as well, that the power to shape worlds is not actually a requisite for winning the fear or adoration of an ancient civilisation. Tornadus, Thundurus and Landorus, too, have destructive and protective powers that function on a local rather than a regional or global scale; they are deities of folktale, not epic, a smaller scale of things to which Pokémon, by its very nature, is eminently better-suited.